The Reality and Prospects of Research on Islamic Manuscript Heritage in Nigerian Universities and Research Centers

he speech was given at the international scientific symposium organized by the Mohammed VI Foundation of African Oulema on the theme of “The African Islamic Heritage: Memory and History” on 22-23-24 Rabi’ al-Awwal 1443 H, corresponding to 29-30-31 October 2021 in the Nigerian capital Abuja.

Abstract

It is indubitable that the area, which subsequently became the Federal Republic of Nigeria, had been one of the earliest regions in West Africa with considerable number of Islamic manuscript heritage written in both Arabic and Ajami before the arrival of the Europeans in the region. Most of those Islamic manuscript heritages are deposited in both private and public repositories, covering a wide range of disciplines, such as medicine, astrology, astronomy, mathematics, psychology, jurisprudence, prosody, poetry, history, calligraphy, Sufism, etc. Those repositories are essential in the intellectual discourse of present-day Nigeria in particular and West Africa in general; they are also a source of pride for the Nigerian people. Unfortunately, those Islamic manuscript heritages have not only been neglected and abused, but also not widely known by contemporary scholars, largely due to lack of content analysis. This paper, therefore, explores the historical evolution of Nigerian Islamic manuscript heritage. It specifically focuses on the scope, classification, category, location, preservation and significance of this rich heritage. The paper submits that those Islamic manuscript heritages collected and preserved in both private and public libraries in Nigeria constitute a rich source of historical, intellectual and cultural heritage of the people of the country. It finally concludes by advocating for the promotion of recovery, preservation, content analysis and utilization of the body of Islamic manuscript heritage for the production of new knowledge.

Introduction

The geographical area, which is today known as the Federal Republic of Nigeria, has been greatly endowed with a considerable number of Islamic scholars of international repute for several centuries; scholars who composed multiple Islamic manuscripts for the use of the people of their times and for generations yet unborn. Today, most of such Islamic manuscript heritages are kept in both private and public libraries with little content analysis. Similarly, such Islamic manuscripts cover a wide range of disciplines, such as medicine, astrology, astronomy, culture, mathematics, psychology, jurisprudence, prosody, poetry, history, calligraphy, Sufism, geography, to mention but a few. These Islamic manuscripts, if studied and analyzed, could provide solutions to some of Nigeria’s contemporary problems. Unfortunately, many scholars and researchers are not aware of these rich intellectual and cultural heritages because no or little attention is given to them. It is against this background that this paper presents an overview of these Islamic manuscript heritages in order to expose them to scholars, researchers, the public and government for their utilization in the production of new knowledge in Nigeria. The specific purpose of the paper is to further sensitize and enlighten all sectors of the society, especially, the policy makers, on the urgent need for the recovery, conservation and preservation of these rich cultural and intellectual heritages for the development of knowledge. One of the findings of the study is that rich cultural and intellectual heritages are huge across almost all nooks and crannies of the country kept in both private and public repositories, and if utilized, as quickly as possible, they will definitely enhance the present state of knowledge at the tertiary level of education, providing solutions to some contemporary problems in Nigeria. The paper finally submits that poor conservation, preservation techniques and limited financial and material support by government at all levels has led to enormous loss or damage of considerable number of Islamic manuscript heritages in Nigeria.

Nigeria’s Islamic manuscript heritage in historical perspective

History of Islamic manuscript heritage in Nigeria is relatively linked to the introduction of Islam into the area.[1]Therefore, a good starting point for the examination of the history of Nigeria’s Islamic manuscript heritage is the eleventh century or even earlier.[2] It is widely agreed that it was in that century that Islam started to gain acceptance in the Nigerian region through the Kanem-Borno area via the existing centuries-old Trans-Saharan trade. It was during this period that the ruler of Kanem, Mai Umme Jilmi or Humai b. Salemma (circa1085-1097 AD) accepted Islam in 1086. His conversion is attributed to the activities and influence of a renowned Muslim scholar, Muhammad bn Mani who had been in the Mai’s court for many years.[3]Since that time, Islam had been recognized as a state religion in Kanem-Borno up to the arrival of British colonialists in the early twentieth century. Furthermore, Islam, according to the Kano Chronicle, was introduced into Hausaland in the fourteenth century A.D.[4] Sarkin Kano Ali Yaji Dan Tsamiya (1349-1388 AD)[5], according to the Chronicle, was converted to Islam by the Wangarawa[6] (a group of Mande Dyula Muslim merchants and clerics from Mali).[7] Muslim Ulama under the leadership of Shaykh Abdurrahman Al-Zaghaite introduced Islam in Katsina during the reign of Muhammadu Korau (1320-1350 AD). This again is stressing the activities of Muslim merchants, scholars and preachers as agents of conversion in both Kanem-Borno and Hausaland.[8]In comparison to the northern parts of the country, with stronger historical connections to North Africa, the Nile Valley and Arabia, Islam penetrated into the southern parts of Nigeria, particularly Yorubaland in the 18th century or even earlier;[9] and found widespread acceptance as a result of the Sokoto Jihad of 1804.[10]

Islam, being a literate religion and closely related to education, which emphasized the importance of education from its inception in Kanem-Borno, Hausaland, Yorubaland, therefore, witnessed the establishment of two types of schools: Qur’anic or elementary school and Madrasah or advanced or higher school. The patronage of Islam and Islamic education by the general population and its official recognition by the rulers of Kanem-Borno, Hausaland, and Yorubaland greatly promoted learning and scholarship in the respective regions.[11]The committed settled scholars and the influx of itinerant and visiting teachers and preachers immensely promoted the development of Arabic and Islamic education in Nigeria. The scholars, particularly from the Hejaz, Egypt, the Maghreb, Tripoli, and Timbuktu, brought with them new books and new information into the Nigerian area. From the beginning of the fifteenth century, the manuscript book importation and its trade, production of inks and its pots, and rampant copying of texts became a distinctive feature of the Borno society.[12]It was reported that by the sixteenth century, the local scholars, particularly those serving in the royal courts, within the Nigerian area, had begun to write books in Arabic. They mastered Arabic to the extent that they adopted Arabic characters (or modify its sounds to suit the local situation) to write in local languages known as Ajami.[13]

The production of Arabic manuscript in the area which is now known as Nigeria could, therefore, be assigned to the fifteenth century. In Kanem-Borno, for instance, Umar bn Usman had documented the official administrative records of Mai Idris bn Ali (1497-1519 AD), while Imam Ahmad bn Furtuwa, the chief Imam and legal adviser of Mai Idris Alooma (1564-1596 AD) chronicled his master’s administrative and war records in his books titled al-Kitab Ghazawat Borno and al-Kitab Ghazawat Kanem. It is also on record that in the seventeenth century, Muhammad Salih b. Salih composed his work on Birni Gazargamu in 1658; Muhammad al-HajjAbdur-Rahman al-Barnawi (Ajirammi) wrote a book titled Shurb al-Zalal on Islamic religious knowledge;[14] while the eighteenth century witnessed the presence of Shaykh Muhammad al-Wali and Shaykh Tahir b. Ibrahim al-Fallati (also known as Shehu Tahir Fer’oma, d. 1776) who composed a popular poem entitled ‘Fane Fane.’[15]

The Production of Arabic manuscripts in Hausaland began in either the fifteenth century or in the sixteenth century by foreign scholars such as Abd al-Rahman Suqqain and Al-Tazakhti.[16]Subsequently, the works of local scholars began to feature in the seventeenth century in Hausaland, particularly from Katsina. The most famous being Muhammad ibn Sabbagh (d. 1655) also known as Dan Marina whose commentary on al-Wasa’il al-mutaqabbala (al-Ishriniyyat or the Twenties) was written by al-Fazazi. His other well-known work is the Mazjarat al-fityan (Admonition to Young Men). Another indigenous author was Abu Abdullahi b. Muhammad b. Muhammad. Muhammad, popularly known as Dan Masani, is widely regarded as an outstanding disciple of Dan Marina. Like his master, he also wrote a commentary on al-Wasa’il al-mutaqabbala (al-Ishriniyyat or the Twenties). The title of his work is al-Nafhat al-Anbariyah fii halli al-Faz al-Ishriniyyat. There was also a work on history of Ulama in Yorubaland, which is attributed to him. The information at our disposal reveal that other prominent local writers from Katsina during this period were Muhammad b. Muhammad b. Ahmad, better known as Dan Takum; Muhammad b. Muhammad al-Katsinawi al-Fallati (d. 1741); and Shaykh al-Bakri. In the seventeenth century, there were many erudite local scholars of international repute such as Abdullahi Sikka, who wrote al-Atiya li’l-mu’ti (The Gift of the Giver); Baba Kur b. al-Hajj Muhammad al-Amin; Shaykh Jibril b. Umar (d. 1795), who wrote Shifa al-Ghalil (the quenching of the thirst). Perhaps, among the Ulama that wrote several volumes in the nineteenth century were the Sokoto Jihad leaders, namely: Shaykh ʻUthmān Dan Fodio (1754–1817), his brother Abdullahi Dan Fodio (c. 1766–1828), his son Muḥammad Bello (1781-1837) and his daughter Nana Asma’u (1793-1864), each of whom had written in both Arabic and Ajami.[17]

There were a number of literary contributions from Borno scholars during this period as well, such as[18] Muhammad Al-Amin El-Kanemi (1775-1837), who has been identified with three outstanding poetic academic works.[19] Two of them were Nasihat al-hukkam ahl al-fahm and daliyya in celebration of his safe return from Baghirmi.[20] His son, Umar b. Muhammad Al-Amin El-Kanemi (1881) was another prolific writer. He wrote Kitab al-Barnu and others.[21] Other notable Borno writers during this period were Muhammad b. Muhammad al-Kanemi al-Barnawi al-Barkawi who composed many works such as Tafsir surat al-Qadr and Mir’at al-Sa’im and Yusuf b. Abd-Al-Qadir Al-Qarghari (d. 1850) whose works were numerous but the most widely known was Burdat al-Jimiyyah fi madḥ Khayr al-Bariyya.[22]

However, one of the most significant moments in the history of indigenous manuscript production in Nigeria was in the twentieth century. The century saw the production and proliferation of Tijānīyya writings from all over the country. For instance, in Kano, there were Shaykh Abū Bakr al-ʿAtīq (d. 1974); Shaykh Abū Bakr Mijinyawa; Shaykh Hassan Na Muḥammad Thani; Shaykh ‘Uthmān Mai Hula (d. 1987); Shaykh Tijjani ‘Uthmān; Shaykh Ahmad Anwar (d. 1973); and Shaykh Sani Kafanga, who composed numerous works.[23]In Nguru (present Yobe State), Shaykh Muḥammad Ghibrīma al-Dāghirī al-Ghūrāwī (1902-1975) composed several works.[24]His magnum opus and perhaps the most celebrated of his writings was Jihaazus Saarih was-saa’ih was-saabih wal aakifilFaalih fid-Taujeehaati bi salaatli faatih SAW (The Treasure of Journey to Allah’s Provision of a Traveller by Road and by Sea and a wayfarer and the Settler on Prayers upon the Prophet (PBUH). Another Nguru scholar who wrote extensively was Sheikh ʻUthmān al-Fallātī (1909-1996).[25]In Maiduguri, for instance, Shaykh Sharrif Ibrahim Salih al-Husayni (b. 1939) has composed more than three hundred works on various branches of Islam.[26] In Bauchi, there is Shaykh Dahiru Usman Bauchi. In the southern part of the country, scholars such as Shaykh Abū Bakr bn Qasim (popularly known as Alufa Alaga); Shaykh Harun bn Sultan Matanmi (d. 1935); Shaykh Baniyamin Adisa bn Tahir bn Malik al-Huayn Motala of Ibadan, Oyo State (d. 1959); Shaykh Yaqub bn Abdulrahman bn Muhammad Mulktar al Imam of Ikirun, Osun State (d. 1965), etc. had contributed a lot in the production of Islamic manuscripts in both Arabic and Ajami scripts.[27]

Scope and Categories of Islamic manuscript heritage in Nigeria

Most researchers classify Nigeria’s Islamic manuscript heritage into two main categories: (i) The works authored by foreign scholars written in Nigeria or brought into the country especially during the pre-colonial period; and (ii) the works authored by Nigeria’s indigenous scholars. Even though this classification of Nigeria’s Islamic manuscript heritage is by no means authoritative, a careful examination of those rich intellectual works, and of the extensive researches relating to them, would find the categorization workable.[28]This categorization of Nigeria’s Islamic manuscript heritage will not only help in the process of acquisition, recovery, preservation of this rich heritage but also aid in knowing what constitutes the heritage itself.

-

Foreign Islamic manuscript heritage

The first category of Nigeria’s Islamic manuscript heritage are works authored by foreign scholars written when they lived in Nigeria or brought into the Nigerian area, especially during the pre-colonial period before the indigenous authorship. There were many foreign scholars who came to the Nigerian area, settled and authored a considerable number of works. For instance, Abd al-Rahman Suqain, the Moroccan scholar, was said to have come and authored some works. He was said to have settled and taught in Kano. Al-Tazakhti was another foreign scholar who came to Hausaland, settled and taught in Katsina. Added to this, are works brought into the Nigerian area by local, itinerant or visiting scholars. Most of the visiting scholars came into the Nigerian area with their books on various subjects which were used in teaching their disciples.[29]Muhammad bin Abd al-Karim al-Maghili who came to Hausaland in the late fifteenth century, brought some works on Maliki law and on Qadiriyya, probably written by al-Ghazali.[30] He also wrote a treatise entitled: Taj al-din fi ma yajib ‘ala I-muluk (The crown of religion concerning the obligations of kings). Some examples of these books were Risalah of Abi Zayd of Qayrawan (d. 996),[31]al-Ishriniyyat (the Twenties) of al-Fazazi, Mukhtasar of Khalil b. Ishaq, Sahih Bukhari, Sahih Muslim, Muqaddimah of Ibn Khaldun, to mention a few.[32]The works which covered various branches of Islamic knowledge and philosophy are kept in public and private repositories, and considered Nigeria’s Islamic manuscript heritage.

-

Indigenous Islamic manuscript heritage

The second category of Nigeria’s Islamic manuscript heritages are works originally authored by the Nigerian indigenous scholars.The subjects of these works may be initiated by the writers themselves like Ihya’us Sunnah of bin Fodio and Infaq al-Maysur of Muhmmad Bello. The works may also be a summary, versification or commentary on the existing works of other authors like the famous work of Muhammad ibn Sabbagh (d. 1655) entitled al-Wasa’il al-mutaqabbala (al-Ishriniyyat or the Twenties) written by al-Fazazi. These works written by local scholars who belonged to the area which is now Nigeria could be categorized in terms of genres, content, authorship for their easy preservation and production of new knowledge. They were first grouped into two main categories: Qur’anic and Non-Qur’anic manuscripts.

- 1-Nigeria’s Qur’anic manuscripts

The first category of Nigeria’s Islamic manuscript heritage is the one pertaining to Qur’anic studies. This is based on the local tradition of Nigeria which requires any memorizer (hafiz) to write his own copy of the Qur’an off heart. The first indigenous Qur’anic manuscript produced in Nigeria was from Borno and it was dated 1669.[33]However, Major Denham in the nineteenth century reported that copies of the Borno Qur’an were exported to North Africa and Egypt, where they were sold for between forty to fifty Maria-Theresa dollars in1822.[34]Nigeria’s Islamic manuscript heritage could be categorized into Plain Qur’anic manuscript and Non-Qur’anic corpus.

-

- The Plain Qur’anic manuscripts

The plain Qur’anic manuscripts are manually reproduced by the graduates of Qur’anic schools who have memorized the whole Qur’an by heart. By Plain Qur’anic manuscript, it simply means the un-translated, un-annotated, uncommented or in broader perspective, the Qur’an without exegeses. This Qur’an is a personal record of a student’s achievement, which he may keep for himself, sell or donate it to his teacher, father, or school.[35] The primary function of Qur’an as a written manuscript, like any other handwritten Qur’an in Nigeria and other parts of the world, is for recitation and teaching. Hence, certain mnemonic devices have been developed to aid the reciters that have become part of the Qur’anic tradition and its calligraphic arts in Nigeria known as Zayyana.[36]These documentary heritages are scattered all over the country but they are neglected for quite a long time.

-

- Ajami/Tarjamo Qur’anic manuscripts

Ajami/Tarjamo Qur’anic manuscripts are Qur’anic texts which were rendered or translated into one of Nigeria’s local languages.[37] Hausa, Fulfulde, Kanuri and Nupe are four major languages which are prominent in the use of Ajami in Nigeria. Today, there are a considerable number of these Ajami/Tarjamo Qur’anic manuscripts kept in both private and public repositories inside and outside the country. In Nigeria, for instance, they are available in almost all the traditional scholars’ residences and many public libraries, research centres, archives such as Arewa House Kaduna. According to El-Miskin, some of these manuscripts are also kept in the School of Oriental and African Studies, London.[38]Today, it is an obvious fact that this kind of manuscript can also be found in private collections of traditional scholars or in possession of their heirs, but no attempt has been made by the governments at all levels to collect and preserve them.

-

- The Tafsir (Qur’anic exegesis) manuscripts

The Tafsir Qur’anic manuscripts are commentaries of the Qur’an by Nigerian local scholars. As pointed out by El-Miskin, these commentaries are quite different from Ajami/Tarjamo Qur’anic manuscripts, because the former are legal interpretations of the Qur’an (better known as tafsir or Qur’anic exegesis); while the latter are mere translation of the Qur’an into any other language.

-

- Annotated Qur’anic manuscripts

The plain Qur’anic manuscripts with annotations, notes or glosses in either Arabic or Ajami (Hausa, Fulfulde, Kanuri Nupe and Yoruba) are of various levels. The annotations, notes or glosses may be anecdotal expansions, explanations, statistical occurrences of Qur’anic words or phrases (haraji).[39]

- 2-Nigeria’s Non-Qur’anic manuscript

These Islamic manuscript heritages are hand-written literary works authored by the Nigerian local scholars, composed in either Arabic or Ajami using Maghreb style of writing kept in the collections of an archive or private and public collections.[40]These works contain prose, poetry, correspondences, and talismanic works which cover the wide range of subjects previously described. The subject of these literary works might be initiated by the authors or commentary, polemic. These rich heritages are reliable sources of information on intellectual, political, economic, social and cultural history of the peoples of the country; and they are also relevant for the construction of history of the peoples and their respective communities.

- These categories of Nigeria’s Islamic manuscript heritage are products of indigenous authorships which consist of prose, poetry, stories, history, etc. The subjects of these were originally initiated and written down by Nigerian indigenous scholars. Good examples of these works are Ibn Furtuwa’s al-Kitab Ghazawat Borno and al-Kitab Ghazawat Kanem; Abdur-Rahman al-Barnawi’s (Ajirammi’s) Shurb al-Zalal.

- Another category of Nigeria’s Islamic manuscript heritages are foreign books, pamphlets and correspondences imported into the Nigerian area and manually copied by the indigenous professional copyists. Most copies of the foreign books were owned by private individuals who started collecting them, presumably when they went on pilgrimage, or when merchants could use the efficient parcel post set up by the new colonial authorities in the beginning of the twentieth century. Therefore, any manuscript book which came into the Nigerian area was immediately circulated among the local scholars and their students by lending, especially to those who either had no access to them or could not afford them. The alternative to importing books is, of course, either to copy them by oneself or engage the services of professional copyists in a few days to possess them.[41]This important development, has therefore, led to the emergence of a large body of professional copyists and calligraphers (warraqun in Arabic) with good handwriting, especially among the ‘Ulama. Most of these hand-written copies of the already existing texts are fiqh (Jurisprudence) manuals for teaching and learning, such as Mukhtasar of Khalil b. Ishaq, Risalah of Abi Zayd of Qayrawan (d. 996) or Hadith collections like Sahih Bukhari, Sahih Muslim.[42]

- Correspondences were another category of Nigeria’s Islamic manuscript heritage which may take many forms. It might be a fatwa on religious matters; debate between rulers, scholars, or students; polemic exchanges, recounting an event or history; appointments, instructions, notices, wills, records of inheritance; Mahram[43] and other forms of communications.[44]Good examples of this category are series of correspondences between Shaykh Muhammad Bello of Sokoto and Shaykh Muhammad Al-Amin Al-Kanemi on the justification of Jihad on Borno.

- Another of Nigeria’s Islamic manuscript heritage is legal or court documents written in Arabic or Ajami. This rich intellectual heritage constitutes the court proceedings or judgments which usually denote the legal erudition of the judges, nature of social, civil, criminal, legal conflicts which can be used for the construction of intellectual and legal history of Nigeria.[45]

- Friday and Eid sermons constitute another category of Nigeria’s Islamic manuscript heritage. These rich intellectual heritages were produced by the Imams for Friday prayer, Eid El-Fitr or Eid El-Kabir occasions.

- The last but not least category of Nigeria’s Islamic manuscript heritage is the annotations and notes on foreign and indigenous books, pamphlets and correspondences. For instance, by the late fourteenth century, the letter from Mai of Kanem to Mamluk Sultan Barquq al-Zahir in Cairo which al-Qalqashandi commented upon is a clear handiwork of Borno copyist and scribes.[46]

Location of Islamic manuscript heritage in Nigeria

Nigeria’s Islamic manuscript heritages are largely found all over the country deposited in private and public libraries, research centres, archives, etc. There are many manuscripts in the hands of scholars, Imams and religious holdings kept in their personal libraries, families’, disciples’, researchers’ and public depositories. A number of private collections are all over the country. In Maiduguri, for instance, where I am working, we have Shaykh Ibrahim Saleh al-Hussainy collection, Shaykh Abubakar El-Miskin collection, Shaykh Ahmad Abdulfathi collection, Shaykh Imam Wafchama collection, and the collections of many other individual scholars in the city. In Nguru, where I come from, we have Shaykh Muhammad Ghibrīma collection and Shaykh Uthman al-Fallātī collection. In other cities of the country as well, especially Kano, Zaria, Sokoto, Katsina, Sokoto, Bida, Ibadan, Ilorin, etc. the houses of most of the recognized traditional Islamic scholars contain private collections with substantial amount of Islamic manuscript heritages. The private copies could also be found in libraries of some Emirs, merchant/traders and traditional chiefs who might have received them as gifts from Arab merchants or purchased them.

The public collections are also available in almost all parts of the country. Some of them are: National Archives, Ibadan; National Archives, Kaduna; Centre for Trans-Saharan Studies, University of Maiduguri; Arewa House, Kaduna; Jos Museum; Centre for Arabic Documentation of the Institute of African Studies, University of Ibadan; Ilorin History and Culture Bureau; Postgraduate Research Unit, Bayero University, Kano; Waziri Junaidu History and Culture Bureau, Sokoto; Centre for Islamic Studies Specialist Library, Usman Danfodiyo University, Sokoto; Northern History Research Scheme, A.B.U. Zaria; Centre for Ilorin Manuscript and Culture, Kwara State University, Malete; Abdullahi Gwandu Library, Sokoto, Kebbi State History Bureau, Birnin Kebbi, etc.

Preservation of Nigeria’s Islamic manuscript heritages and Problems with it.

Preservation simply means the “acquisition, organization and distribution of resources to prevent deterioration or renew the usability of selected groups of materials.”[47] The acquisition, preservation and documentation of the Islamic manuscript heritages will tremendously help in understanding the various dimensions of the intellectual history of Nigeria. Thus, the act of preservation has been of much concern to stakeholders both individual scholars and government officials. Firstly, in pre-colonial Kanem-Borno and Hausaland, scholars and Muslim leaders were responsible for the preservation of manuscripts. The scholars, for instance, being the custodians of their manuscripts, were responsible for the circulation and protection, even in the midst of war. The care and preservation of public collection of these manuscripts was done by Muslim rulers and most of the manuscripts collected were kept within the courts in cities such as Birni Gazargamu, Kano, Katsina and Ilorin under the official care of either court officials or the scribes in their personal libraries.[48]While in Sokoto, the Waziri was the absolute custodian of the official records and other important documents, and the scholars took utmost care of their works.[49] This tradition of protection and preservation of manuscripts continued until the arrival of European explorers.

With the advent of the Europeans, they started collecting manuscripts for the useful information about the various peoples, cultures, places of the Nigerian area which can be found in the manuscripts which were scattered all over the area under the official custodians and individual scholars. The 19th century traveler Heinrich Barth, for instance, was said to have an insatiable quest for manuscripts during his visit to Borno in the 1850s. He was said to have collected many manuscripts whenever he heard of them.[50]In fact, Barth did not only collect the manuscripts, but also served as a copyist in Borno.[51]It is speculated that most, if not all, of the manuscripts he collected were taken to Europe for content analysis.[52]

Similarly, following the imposition of colonial administration from 1st January, 1900 in the Nigerian area, the colonialists embarked on collection of manuscripts for the required information for the success of their administration and tagged them as Nigeria’s historical records.[53] This development led to the establishment of National Archives and Research Institutes for the collection and preservation of manuscripts and other important documents.[54]In the 1950s, the colonial government intensified its effort and a considerable number of manuscripts were collected and preserved. It was as a result of this effort of colonists that the indigenous scholars engaged themselves in the recovery, preservation and thorough study of these manuscripts.

With the attainment of Nigeria’s independence on 1st October, 1960, the responsibility of preserving these manuscripts continue to be held on both individual scholars and Nigerian government officials. The government continued with what the previous governments started and many manuscripts were collected and preserved in the 1960s. Afterward, a number of higher institutions were established in major cities of the country such as Ibadan, Zaria, Kano, Sokoto, Jos, Ilorin, and Maiduguri, which in their efforts established sections for the retrieval, preservation and conservation of manuscripts.[55] However, there are also a number of State Archives, Museums, Bureaux and Research Centres which were established and saddled with responsibilities of recovery, preservation and study of these manuscripts.

Some of the problems of preservation of Nigeria’s Islamic manuscript heritages are as follows:[56]

- One of the problems associated with preservation of Nigeria’s Islamic manuscript heritages is the lack of seriousness from the government in heritage preservation. For instance, despite the efforts of previous governments and researchers, there are still a large number of manuscripts in the hands of families and private collections scattered all over Nigeria. Majority of these manuscripts were poorly kept and under the danger of termites, bad weather and other insects damaging these Nigerian Islamic manuscript heritages. Saeed recounts that some of the manuscripts in private collections were reduced into ashes by fire and cites Malam Boyi’s repository as an example.[57]

- In relation to the above, there are individual scholars who possess valuable manuscripts but refuse to make their collections to researchers and government officials.

- As earlier mentioned, there are a large number of manuscripts which were taken by the European explorers and colonial masters and never returned.

- There are considerable numbers of manuscripts which were collected and preserved in the National Archives, Research Centres, Museums, Bureaux, etc. Unfortunately, they are poorly handled without utmost care, not minding that manuscripts are quite The ones which were microfilmed are now largely damaged, especially those in Kaduna National Archives and University of Ibadan.[58]

- Another problem is the limited financial and material support from governments at all levels.

These problems of poor preservation techniques have been contributing immensely to damage of Nigeria’s Islamic manuscript heritages.

|

|

|

|

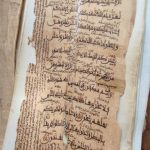

Recently Recovered and Digitalized Goni Musa Mushaf in Gashi Village, Danbatta Local Government Area, Kano State, 2021

|

|

|

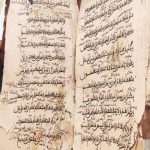

Part of the Collection of one of the Deceased Shaykhs in Nguru Town, Yobe State, 2019

Importance of Nigeria’s Islamic manuscript heritages

The importance of Nigeria’s Islamic manuscript heritage cannot be overemphasized. The Islamic manuscript heritage can be used in teaching and learning all branches Islam. In fact, if these Islamic manuscript heritages are revisited for research, for instance, when translated, edited and analyzed as quickly as possible, they will definitely enhance the present state of knowledge at the tertiary level of education in Nigeria and indeed the whole of Africa. However, these Islamic manuscript heritages have important bearing on the intellectual, political, economic, social and cultural heritage of the peoples; and have contributed to the understanding of the history and culture of the peoples of not only Nigeria but also those of other parts of Africa.

This is because these rich documentary intellectual heritages are authentic source of reliable information on intellectual, socio-economic, cultural and political history of the peoples of Nigeria. For instance, the Qur’anic manuscript heritages, without doubt, reveal the design, script and its modes, history, artistic decoration (zayyana) of pre-colonial Nigeria’s Qur’anic manuscript heritage which will be used in construction of region’s calligraphic and intellectual history. It will also help in identifying the level of competence in Qur’anic studies in the region; identify the writers and period of writing.[59] In relation to this, the region’s leatherwork, paper type and inks will also be tapped from the Qur’anic manuscript heritage.

Similarly, the non-Qur’anic manuscript heritages expose the calligraphic traditions and writing systems of the pre-colonial Nigeria intellectual heritage. They also contain the recordings of intellectual history of the periods in which they were produced. It also reveals the texts, curriculum, the best sellers and reading culture of the period in which they were produced. For instance, legal manuscript heritage depicts the legal erudition of the judges, nature of social, civil, criminal, legal conflicts which can be used for the construction of intellectual and legal history of Nigeria.[60]

Conclusion

This paper explores the historical evolution of Nigeria’s Islamic manuscript heritages, including their scope, classification, category, location, preservation and importance. From the discussion, it is clear that rich cultural and intellectual heritages are huge across almost all nooks and crannies of the country kept in both private and public repositories, and if utilized, as quickly as possible, they will definitely enhance the present state of knowledge at the tertiary level of education providing solutions to some contemporary problems in Nigeria. This, as we earlier explained, has shown that poor conservation, preservation techniques, limited financial and material support by government at all levels led to enormous loss or damage of a considerable number of Islamic manuscript heritage in Nigeria. It is for this reason that this paper recommends the followings:

- The government at all levels should endeavor to identify all the locations of the manuscripts, both private and public collections, and make a complete list of them for easy manuscript census in the country, and use modern technology in preserving them properly.

- The government should also come up with new policies and easy ways of retrieving these manuscripts which are still in the hands of individual scholars and families scattered all over the country.

- The government should provide a suitable environment for the preservation of these manuscripts. The infrastructure should be free from insects, harmattan dust, moisture and the shelves metallic instead of wooden as well as the temperature and humidity should not be high.[61]

- The researchers, users and visitors of these manuscripts should handle them with utmost care. Better still, people should not write on them and spill water, tea or coffee on them. To the individual scholars, the traditional method of preserving these manuscripts such as laminating them with liquid and solid tape or using thread to sew them when torn should be stopped at all cost.

- The National Archives, Research Institutes, Museums, Bureau should provide maximum security to these manuscripts.

- The stakeholders concerned should continue to enlighten the public and policy makers about the importance of Nigeria’s Islamic manuscript heritage and urgent need for their preservation got the development of new knowledge.

References

[1]Batiste 2007; Saeed 2010:24.

[2]Hogben 1967:50. The precise date when Islam penetrated into the region now known as Nigeria is yet to be determined by scholars, largely due to the absence of concrete evidence. The most reliable date of the presence of Islam in Nigeria, to the researcher’s knowledge, has been the eleventh century.

[3]See Lavers 1971:28; Alkali 2013: 39-44. Although the presence of Muslims in the Kanem-Borno region had definitely predated the 11th century (which marked the public acceptance of the new faith by Mai Umme Jilmi), this conversion was spectacular. For instance, Muhammad bn Mani is reported to have taught Qur’anic recitation, while Tura Tazan taught its calligraphy (see Dahiru 1995:141).

[4]Palmer 1967, III: 79; Orr1965: 256.

[5] Muhammad 1981: 6.

[6] Adamu1999:37.

[7] Balogun1980: 213.

[8]Adamu1999: 37.

[9] Jimba 2019:1

[10]Saeed 2010: 28.

[11]Saeed 2010:26.

[12] El-Miskin 2009: x.

[13]Hausa, Fulfulde, Kanuri, Nupe and Yoruba are five languages which are prominent in the use of Ajami, perhaps due to a sizeable number of the speakers’ literacy in Arabic. Diso 2010: 101; Saeed 2010:26.

[14]Saeed 2010:26.

[15]Saeed 2010:26.

[16] Adamu 2010:160.

[17]Many writers have prepared long list of the titles of their works see Saeed 2007, 2010: 46-52.

[18]For detailed and elaborate information on Borno scholars and their literary works see Hunwick 1995.

[19] Majority of his write-ups were correspondences.

[20] For his biographical notes and list of his works see Hunwick 1995: 384-387; see also Dahiru 1995: 51-52 & 80.

[21] See Hunwick 1995:387.

[22] Dahiru 1995: 54.

[23]See Hunwick 1995 and Brigaglia 2013/2014 for the titles of their works.

[24] There is no last word on the actual number of his works due to lack of unanimity in the number of works ascribed to him. See Hunwick 1994: 406-407; Al-Qadiri 1979; Tahir 2006: 86-89; Sanda 2016; Idris 2010:75; 2017:189-194 and Al-amin 2020. In March, 1988, when I was an assistant lecturer in the Department of History, University of Maiduguri, I went to Nguru for a fieldwork and I was able to get some manuscripts which consisted of works of al-Dāghirī. I also interviewed Imam Ahmed, Ba Malam Kanta, a contemporary of al-Dāghirī, Zanna M. Ali, the District Head of Nguru, al-Fallātī, a renowned scholar in Nguru and Sheriff Tahir, a leader of the Izala Movement in the town. For details, seeCentre for Trans-Saharan Studies, University of Maiduguri, Progress Report, No. 2, Sept., 1988: 28.

[25]See Hunwick 1995 and Brigaglia 2013/2014 for the titles of their works.

[26] The number of works ascribed to him varies from one researcher to another. For instance, Hunwick attributed ninety-five works to him (see Hunwick 1995:407-415).

[27] I am extremely grateful to Professor Yahya Oyewole Imam of the Department of Religions, University of Ilorin for furnishing me with this information.

[28] For more detailed information on provisional classification of Nigeria’s Islamic manuscript heritage specially made for their easy retrieval see El-Miskin 2007; see also Adamu 2010:158-164.

[29] For comprehensive list of their works see Kani 1978; Ahmed 1986.

[30] Hiskett 1975:73; Paden, 1973:65.

[31] Mahmud 1983:37.

[32] In fact, the works of foreign scholars which had distributed in almost all parts of Nigeria are tremendously inspired the local scholars and began indigenous authorship.

[33]Bivar 1960; Bondarev 2014:108.

[34] Laminu 1992:10.

[35] El-Miskin 2007:38.

[36]Zayyanain Hausa or fawne in Fulfulde simply means calligraphy on paper, slates, wall, etc. In the context of northern Nigeria, is a decorative arts and calligraphic design in the handwritten Qur’anic and non-Qur’anic manuscripts such as the colourful artistry (pertaining to representing different characters of the alphabets and their vocalisations), the separational artistry of colourful identifications of chapter and section endings as well as many other artistic and printing potentials are abundantly available to assist the reader in knowing the divisions of the text

[37] I have never laid my hand on it but El-Miskin confirmed its existence in Nigeria see El-Miskin 2007: 40.

[38]El-Miskin 2007:40.

[39]El-Miskin 2007:40.

[40]Gwandu 2010: xxvi-xxxii.

[41] It is difficult to ascertain the exact date when the art of copying was introduced into the region due to paucity of written sources, but it is asserted that it might have been introduced into the Kanem-Borno region before the eleventh century. See Dahiru 1995:137.

[42]El-Miskin 2007:40.

[43]The ‘Mahram’ or ‘letter of patent’ is a grant of privileges which exempt the ulama and their families from participating in active services of the town like conscription into the military, payment of taxes, slavery and forced labour, etc, were given some material entitlement. This tradition continued throughout the period of Sayfawa rule and was adopted by the El-Kanemi dynasty in Borno. See Lavers 1971:37-38.

[44]El-Miskin 2007: 42-43.

[45]El-Miskin 2007: 41.

[46] Biddle 2011: 7.

[47]Alegbeleye 2010:85.

[48] Saeed 2010:31.

[49] Saeed 2010:31.

[50] Garba 2016: 59.

[51] Garba 2016: 59.

[52] Garba 2016:59.

[53] Saeed 2010, 31-32.

[54] Saeed 2010:31-32.

[55] Saeed 2010:32-33.

[56]These problems have been discussed in detail by many scholars such as Saeed 2010; Biddle 2008; Abioye 2010.

[57] Saeed 2010: 33-34.

[58] Saeed 2010:33.

[59]El-Miskin 2007: 39.

[60]For details, see El-Miskin 2007: 41.

[61] See Baptiste 2007; Biddle 2008..

Sources

- Aboye, A. (2010): “Promoting the Preservation of Heritage Materials in Nigeria: A Review of Recent Heritage Conference Papers,” In: Ibrahim, Y. Y. et al., eds., Arabic/Ajami Manuscripts: Resources for the Development of New Knowledge in Nigeria, Proceedings of the national Conference on Exploring Nigeria’s Arabic/Ajami Manuscripts, Kaduna: Arewa House, pp.74-84.

- Adamu, M. (2010): “The Scope and Significance of Arabic Manuscripts in Nigeria,” in Ibrahim Y. Y. et al eds., Arabic/Ajami Manuscripts: Resources for the Development of New Knowledge in Nigeria, Proceedings of the national Conference on Exploring Nigeria’s Arabic/Ajami Manuscripts, Kaduna: Arewa House.

- Adamu, M.U. (1999): Confluence and Influence: The Emergence of Kano as a City-State. Kano: Munawwar Books Foundation.

- Alegbeleye, G.O. (2010): “The Conservation and Preservation of Arabic Manuscript Resources for the Development of New Knowledge in Nigeria,” In: Ibrahim, Y. Y. et al., eds., Arabic/Ajami Manuscripts: Resources for the Development of New Knowledge in Nigeria, Proceedings of the national Conference on Exploring Nigeria’s Arabic/Ajami Manuscripts, Kaduna: Arewa House.

- Alkali, Muhammad N. (2013): Kanem-Borno under the Sayfawa: A Study of the Origin, Growth and Collapse of a Dynasty (891-1846), Maiduguri: Borno Sahara & Sudan Series.

- Balogun, S. A. (1980): “History of Islam up to 1800,” In: Obaro Ikime (ed.) Groundwork of Nigerian History, Ibadan: Heinemann Educational Books (Nigeria) Plc. pp.210-223.

- Batiste, A. (2007): “The State of Arabic Manuscript Collections in Nigeria: Report of a Survey Tour to Northern Nigeria,” Washington DC, Library of Congress (March3-19th 2007), pp.3-17.

- Biddle, M. (2008): “Saving Nigeria’s Islamic Manuscript Heritage,” Kaduna: Arewa House.

- Biddle, M. (2011): “Inks in the Islamic Manuscripts of Northern Nigeria: Old Recipes, Modern Analysis and Medicine,” in Journal of Islamic Manuscripts 2, 1-35.

- Bondarev, D. (2014): “Multiglossia in West African manuscripts: The case of Borno, Nigeria,” In: Jörg B. Quenzer, J. B. Bondarev, D. and Jan-Ulrich Sobisch, J., eds., Manuscript Cultures: Mapping the Field, Berlin, Munich, Boston: De Gruyter.

- Brigaglia, A. (2013-2014): “Sufi Revival and Islamic Literacy: Tijani Writings in Twentieth Century Nigeria,” In: Annual Review of Islam in Africa, Issue No. 12/1, pp.102-111.

- Bivar, A. D. H. (1960): “A dated Kuran from Bornu,” Nigeria Magazine 65, pp.99-205.

- Dahiru, Umaru (2011): Qur’anic Studies in Borno: Developments in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, Maiduguri: ED-Linform Services.

- Diso, L. I. (2010): “Nigeria’s Ajami Manuscript Resources for the Development of New Knowledge: The Questions and Management and Access Policies,” In: Ibrahim, Y. Y. et al., eds., Arabic/Ajami Manuscripts: Resources for the Development of New Knowledge in Nigeria, Proceedings of the national Conference on Exploring Nigeria’s Arabic/Ajami Manuscripts, Kaduna: Arewa House, pp.104-115.

- El-Miskin, T. (2007): “Northern Nigeria’s Intellectual Heritage: Methodological Perspectives on Retrieval, Preservation and Access,” In: El-Miskin et al., eds., Arabic/Ajami Manuscripts: Resources for the Development of New Knowledge in Nigeria, Proceedings of the national Conference on Exploring Nigeria’s Arabic/Ajami Manuscripts, Kaduna: Arewa House, pp.24-60.

- Garba, Abdullahi (2016): “The Role of Western Writers on the Historiography of Borno, 1851-1973,” Unpublished M.A. History Dissertation, University of Maiduguri.

- Gwandu, A.A. (2010), “Exploring Nigeria’s Arabic/Ajami Manuscript Resources for the Development of New Knowledge in Nigeria,” Key Note Address, Ibrahim Y.Y., et al., ed., Proceedings of the national Conference on Exploring Nigeria’s Arabic/Ajami Manuscripts, Kaduna: Arewa House.

- Hiskett, M. (1975): A History of Hausa Islamic Verse, London: School of Oriental and African Studies.

- Hogben, S.I. (1967): An Introduction to the History of the Islamic States of Northern Nigeria, Ibadan:

- Hunwick, J.O. (1995): Arabic Literature of Africa II: The Writings of Central Sudanic Africa, Leiden: E.J. Brill.

- Jimba, Moshood M, ed. (2019): Arabic Manuscripts in the Ilorin Emirate, Ilorin: Kwara State University Press.

- Kani, A. M. (1978): “Literary Activity in Hausaland in the Late Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries with Special Reference to Shaykh Uthman b. Fudi (d. 1817),”M. sc. Dissertation, A.B.U., Zaria.

- Laminu, Z. H. (1992): Scholars and Scholarship in the History of Borno, Zaria: The Open Press Ltd, 1992.

- Lavers, John E. (1971): “Islam in the Bornu Caliphate: A Survey,” ODU: A Journal of West African Studies, University of Ife, New Series, No. 5, April, pp. 27-53.

- Muhammad, M. (1981): “Origins and Development of Islam in Kano up to 1810,” B.A Dissertation, Department of History, University of Sokoto.

- Orr, C. (1965), the Making of Northern Nigeria, London: Frank Cass.

- Paden J.N, (1973): Religion and Political Culture in Kano, California: University of California Press.

- Palmer, H.R. (1967), Sudanese Memoirs, New Impression, London: Frank Cass & Co. Ltd.

- Saeed, A. Garba (2010): “Arabic Manuscript Heritage: A Neglected Source of History in Nigeria,” In: Ibrahim et al., eds., Arabic/Ajami Manuscripts: Resources for the Development of New Knowledge in Nigeria, Proceedings of the national Conference on Exploring Nigeria’s Arabic/Ajami Manuscripts, Kaduna: Arewa House, 24-60.